Guy Kinnings, the co-head of IMG golf, remembers a conversation he had with the late Mark McCormack when the latter was talking about the qualities he sought in a potential golf client.

Guy Kinnings, the co-head of IMG golf, remembers a conversation he had with the late Mark McCormack when the latter was talking about the qualities he sought in a potential golf client.

McCormack, who founded his International Management Group in 1960, put talent above all else: “Give me a player with raw talent and we can help with the rest of what’s needed.”

In McCormack’s eyes, the player who had oodles of charisma and good looks but no talent was a non-starter.

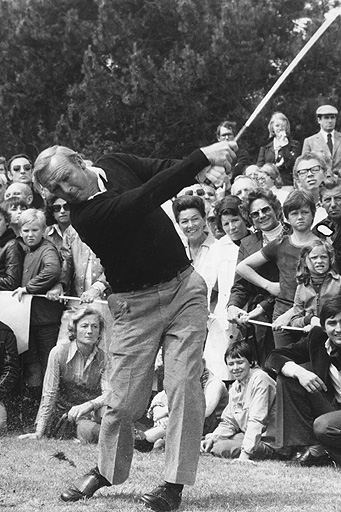

Having joined IMG after a spell as a London solicitor, Kinnings is well-placed to expand on that theme. “Where you have golfers with the talent, the necessary work ethic and the X factor, that’s the optimum,” he says. “That’s what McCormack had with in his first client, Arnold Palmer and it’s the combination which lends itself to building brands and good global marketing and merchandising opportunities.”

Kinnings goes through the list of all-time great IMG clients, some of whom have gone on to build their own empires. After Palmer came Jack Nicklaus and after Nicklaus, Gary Player. Then came Greg Norman, and after Norman, Tiger Woods. As Kinnings says, each in his own way was blessed with everything it takes.

Today, IMG has between 70 and 80 golf clients aged 17 to the octogenarian Palmer, although Woods is no longer part of the fold having followed ex-IMG agent Mark Steinberg to the latter's Excel Sports Management in May of last year. Each is picked and then courted with care.

IMG has its own talent scouts dotted around the world, while the company will also listen to others in the know. On some occasions, it will be a client who has come across a promising youngster on his travels; on another, it will be a member of the press who has a gifted player on his patch.

Again, there will be plenty of would-be clients or their parents who write in to the IMG headquarters.

Kinnings knows what to look for in such letters. While he would not want to deter the child who spends most of his days on the practice ground, he does not want to hear that the boy or girl in question is playing golf to the exclusion of all else. “Things tend to work out better when golf isn’t the be all and the end all in a teenager’s life,” he suggests. “The ones who are best-suited to the life of a professional golfer are those who can compartmentalise and have other things going on – schooling, a good family life and real friends.”

Kinnings cites Padraig Harrington, a major winner who was so astute as to forge an agreement with IMG which stated that the company would give him a job as an accountant if he failed to make it as a golfer.

“If Padraig hadn’t made it,” says Kinnings, “I have no doubt that he would have made his mark in the financial world. He has always known how to compartmentalise. He qualified as an accountant and he also signed off properly from his amateur career, playing in as many as three Walker Cups.

“No professional," continues Kinnings, “works harder than he does but, as I say, he has everything in its place. Golf is far from the only thing in his life. He has a great family, great friends and no shortage of interests.”

He goes on to say that whenever he walked with Harrington to the practice range, the chances were that his player would discuss five or six different topics before getting round to golf. “He’s up to speed on all sorts of things,” says the manager. “When he gives speeches to captains of industry, something he’s done on several occasions, his interest in what they do shines through.”

Kinnings mentions Colin Montgomerie as another in the Harrington mould. Like Harrington, Montgomerie has a university background and, again like the Irishman, he fulfilled his amateur ambitions before turning professional, in his case playing in two Walker Cups.

Montgomerie captained the 2010 Ryder Cup side and made a success of all that entails, and despite his somewhat surly reputation during tournament play, there is apparently no-one more in demand as a Pro-Am partner than Monty.

Kinnings sees Lee Westwood, from the rival ISM stable, as someone else who has grown off the course as much as on in his playing years and has what it takes to put Pro-Am partners and everyone at ease.

Much the same applies to world number one Luke Donald.

Here, Kinnings makes specific mentions of the player’s artistic talents. Englishman Donald, who studied art at Northwestern in Chicago, painted a programme cover for the Western Open on at least one occasion – and has a genuine interest in art in general.

Kinnings recalls listening with interest to the tributes Donald paid to his father who died towards the end of last year. “Luke,” he remembers, “said that his father had been proud of his golf but that he had always been more interested in his development as a person, which is as it should be.”

Matteo Manassero, who still takes time out from the circuit to sit school exams, and Tom Lewis, are two of IMG’s more recent signings and Kinnings could not be more impressed with either. “The two of them came virtually ready-made,” he marvels.

Manassero speaks four or five different languages and, like Harrington and Montgomerie, made a presentation to the International Olympic Committee when the various golfing bodies were seeking to have golf included in the Summer Games of 2016. “He was only sixteen at the time but he was an absolute stand-out,” says Kinnings.

The IMG man knew that Lewis already had the so-called ‘X factor’ but even he marvelled at the interview which the 21-year-old gave at Royal St George’s following the 65 with which he shared the first-round lead of the Open. He knew, instinctively, what to say, not least when it came to talking about Tom Watson, his playing companion and the golfer after whom he was named. At the same time, he knew to thank everyone who had helped him in his amateur career, including his family and the English Golf Union.

“Neither Matteo or Tom is limited to talking about birdies and bogeys,” says Kinnings, before paying tribute to the way they were raised.

Kinnings has no doubt that it is tough for the parents of a potential star to get things right.

“It’s exciting to have a gifted child, of course it is,” he says. “What the parents must do is to allow that talent to grow but not at the cost of everything else. They have to make sure they are not running an oppressive regime; that they are giving their offspring the chance to develop as people."

Kinnings stresses that IMG is not in the business of dragging boys and girls out of school and out of the amateur game. “For the most part,” he begins, “we want to see them carrying on with what they have been doing uninterrupted. If players have got to the top of the amateur ranks, the chances are that the set-up is excellent already. They probably have the best in support from family and friends and they will almost certainly be working with a good coach.

"We look to build on what they have and to give them the opportunities and financial help they might need at the outset of their careers."

Since IMG run between 45 and 50 men’s and women’s tournaments every year, they are ideally-placed to give playing opportunities to up and coming clients. All of which can be hugely important where, say, a player has missed out at qualifying school and is struggling for openings.

You ask Kinnings if IMG see anyone who has won the Open Championship as someone they would want on their books and he explains that the Open champion label has a cachet which makes for good business every time. Yet he insists that he would not dream of putting another client’s nose out of joint in a bid to get the player in question.

“The most satisfying scenario,” he says, “is when you have a client with whom you stick through thick and thin, and who eventually comes through to achieve his dream.

“That’s the ultimate.”

Click here to see the published article.