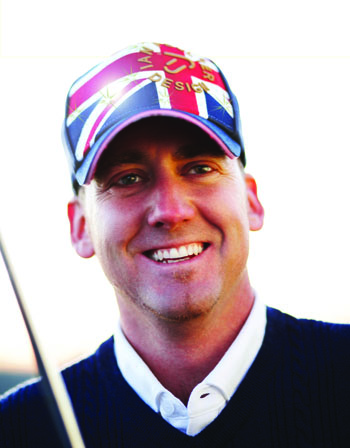

Graduating to the European Tour after successfully emerging from the rigours of qualifying school the next year, Poulter found almost instant success by winning the 2000 Italian Open, a result which helped earn him the coveted Sir Henry Cotton Rookie of the Year award. But despite five more victories over the next four years – including the prestigious season-ending Volvo Masters in 2004, where he beat Sergio Garcia in a sudden death playoff – the 6ft 1in Poulter was making more headlines as a result of his comments and on-course behaviour than he was for his form. “I always speak my mind,” says Poulter, suddenly serious. “I’m always going to say it how it is. It might not always be PC [politically correct], but I don’t agree with being PC just for the sake of it. I’d rather be honest.”

Graduating to the European Tour after successfully emerging from the rigours of qualifying school the next year, Poulter found almost instant success by winning the 2000 Italian Open, a result which helped earn him the coveted Sir Henry Cotton Rookie of the Year award. But despite five more victories over the next four years – including the prestigious season-ending Volvo Masters in 2004, where he beat Sergio Garcia in a sudden death playoff – the 6ft 1in Poulter was making more headlines as a result of his comments and on-course behaviour than he was for his form. “I always speak my mind,” says Poulter, suddenly serious. “I’m always going to say it how it is. It might not always be PC [politically correct], but I don’t agree with being PC just for the sake of it. I’d rather be honest.”

One example of this honesty came eighteen months ago when he told a British golf magazine: “The trouble is I don’t rate anyone else. Don’t get me wrong, I really respect every professional golfer, but I know I haven’t played to my full potential and when that happens, it will be just me and Tiger.” In the ensuing aftermath, Poulter was widely berated by the media, who accused him of supreme arrogance and, well, being a bit of an egotistical prat. But while the Hertfordshire native certainly wouldn’t win any awards for modesty, there’s a lot more to him than the brash peacock he’s made out to be. Over the course of the interview, Poulter was humorous, polite, thoughtful and even sensitive. I wasn’t sure what to expect prior to our meeting but he was thoroughly engaging – and no more so than when the chat moved on to his involvement with Dreamflight, a UK-based charity whose purpose is to take seriously ill and disabled children on a ‘Holiday of a Lifetime’ to the theme parks of central Florida.

Poulter, who has three children of his own, is one of the charity’s largest donators and plays an active role by greeting the 300 children off the plane and joining them for their days out at Disney World and Universal Studios. “It’s an incredible thing,” says Poulter, “and it’s very emotional. The charity does a brilliant job in giving the kids a great holiday, and they’re really great kids. But at the back of your mind you know that because of their illnesses you might not see them again the next year.” He pauses for a few moments, seemingly uncertain about how to continue. “But from the moment I heard about what Dreamflight was all about I wanted to be involved. I find it hard doing interviews about it without getting emotional, to be honest, but it’s really important that more and more people read and understand more about the charity. They enable a lot of deserving kids to have a lot of fun. At the end of the day, that’s what life should be all about.”

Poulter, one thinks, appreciates this more than most.

Pages

Click here to see the published article.